Sometimes I think the biggest risk in investing isn’t the market at all, it’s the human brain. People with advanced degrees and complex careers will walk straight into decisions that make zero sense on paper. Not because they’re reckless, but because money has a strange way of rewiring our logic. A headline rattles us, a bad week in the market bruises our ego, a good year tempts us to tinker, and suddenly even the smartest people start making choices they’d never recommend to anyone else.

Most bad financial decisions come not from lack of knowledge, but from psychology. And unless you understand how your own mind tries to trip you up, you can end up sabotaging yourself without even realizing it.

This article is about those mental traps, the biases that sneak into our judgment, and why even brilliant people aren’t immune to them. It’s also about how to keep those instincts from steering your financial life, and help ensure we keep your financial plan behind the steering wheel.

Why Intelligence Isn’t Enough

We’re not Vulcans from Star Trek, making perfectly logical, emotion-free decisions. When it comes to money, our brains often betray us. There’s an entire field of study behavioral finance that shows how our decisions are influenced by cognitive biases, the systematic ways our minds deviate from rationality.

Let’s talk about three of the biggest culprits: loss aversion, recency bias, and confirmation bias. These technical terms describe very human tendencies that can lead even brilliant people to make not-so-brilliant choices with their investments.

Loss Aversion

Neuroscientific research shows that financial losses activate the brain’s fear center, and can even trigger stress responses similar to physical pain. Functional MRI studies reveal that potential losses evoke stronger emotional reactions than gains of equal magnitude, leading to more impulsive, protective decisions.

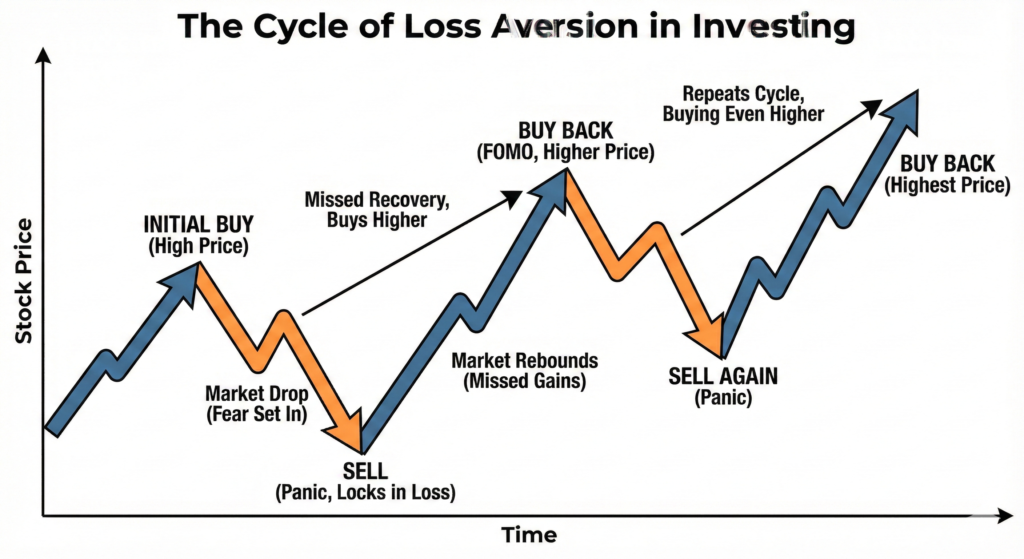

For example, have you ever sold a stock or fund in a panic because it dipped, only to regret it later? That gut-wrenching pain you feel seeing your investments go down is loss aversion in action. Losing money hurts. In fact, the pain of a loss is about twice as powerful as the pleasure of an equivalent gain.

No wonder we’ll do almost anything to avoid that sting. On a side note, if you damage your amygdala, you might even stop worrying about financial losses.. but we don’t recommend hitting your head against the wall to make yourself a better investor.

But I see this all the time. A client’s portfolio drops 5% in a market correction, and suddenly they want to retreat to cash, locking in the loss. It doesn’t matter that their plan is long-term or that the market has historically recovered; in that moment, fear takes over. Even smart investors aren’t immune. If anything, a highly analytical person might vividly calculate just how many dollars they’re “down” and panic even more.

The irony is that this bias can cause the very harm it seeks to avoid. By fleeing at the first sign of trouble, you might avoid a bit of pain today, but you potentially miss out on the gains when the market rebounds. Worse, you could end up back in at higher prices later.

Every loop of this cycle widens the gap between market returns and your returns. You can be invested in the very same market as everyone else and still lag far behind simply because you keep getting shaken out at the wrong moments. That’s why long term data shows such a stubborn performance gap between buy-and-hold investors and the average investor who lets emotions steer the wheel.

Recency Bias (Overvaluing the Latest Information)

Recency bias is our tendency to give more weight to recent events and experiences, forgetting that things can change. If the market has been up for a few years, we start to believe it’ll go up forever. If it just tanked last month, we feel like the sky is falling and it’ll never stop. We react to whatever just happened as if that’s the new normal.

Recency bias tempts us to time the market, usually with poor results. We chase performance, buying whatever’s been hot lately, or we sell in anticipation of bad news after a downturn. Both moves can be damaging, because if you jump in and out of the market trying to avoid downturns, you risk missing the best days when the market rebounds. And missing just a few of those top days can wreck your returns.

For example, an analysis found that an investor who stayed fully invested for 20 years far outperformed someone who missed only the ten best days in the market during that period.

Impact of Time Out of the Market

Invested

Best Days

Best Days

Best Days

Best Days

Best Days

Best Days

Growth of $10,000 invested in the S&P 500 over 20 years. Missing just a handful of the market's best days can dramatically reduce your long-term returns.

The chart above shows what happens to a $10,000 investment in the S&P 500 over 20 years depending on how many of the market’s best days you miss. An investor who stayed fully invested from 2004 to 2023 would have seen their money grow to $63,637, earning an average annual return of 9.7%. But here’s where it gets painful. Missing just the 10 best days during that entire two-decade stretch cuts your ending balance to $29,154 and drops your annual return to 5.5%.

That’s less than half of what the patient investor earned. Miss 20 of the best days and you’re left with $17,494 and a meager 2.8% annual return. And if you managed to be out of the market for 40 or more of its best days? You’d actually lose money. Your $10,000 would shrink to $8,048 or less, turning what should have been impressive long-term growth into a negative return.

The takeaway is clear. Those best days aren’t evenly spread out across the calendar. They tend to cluster right around the worst days, which means the investors most likely to miss them are the ones who sold in a panic and were waiting on the sidelines for things to “calm down.”

Confirmation Bias (Only Hearing What You Want to Hear)

The third troublemaker is confirmation bias, our natural inclination to seek out information that confirms what we already believe and ignore the rest. Neuroscientific studies show that when people encounter information that aligns with their beliefs, the brain’s reward centers light up, particularly the ventral striatum, reinforcing the pleasure of being “right.” Meanwhile, contradictory evidence triggers cognitive dissonance and is often mentally discarded to protect our existing worldview.

Therefore, once we form an opinion, especially about an investment, we love to say “See, I knew it!” Humans are story-loving creatures. We pick a narrative (“This stock is going to the moon” or “The economy is doomed”), then cherry-pick the news and data that support that narrative.

In investing, confirmation bias can lead to concentrated bets and stubbornly holding onto a thesis even as evidence mounts against it. If you believe that, say, renewable energy is the future (a reasonable view), you might overweight your portfolio with those stocks and ignore warning signs or the need for diversification. Or if you’re bearish expecting a market crash, you’ll find plenty of doom-and-gloom blogs and pundits to reinforce your fear, convincing you to sit in cash while the market quietly goes up. In both cases, you risk tuning out information that could help you make better decisions.

The Cost of Bad Behavior

It might surprise you to learn that the average individual investor underperforms the market indices by a significant margin. Despite having the same opportunities as the overall market, they end up earning far less over time. The reasons being poorly timed decisions: buying high, selling low, and generally letting fear and greed dictate strategy.

Studies find that over long periods, the typical investor’s returns are several percentage points lower per year than the S&P 500’s returns. That gap is largely due to behavioral mistakes, like yanking money out at the wrong time or chasing fads. Little missteps, compounded over time, turn into a big difference.

The greatest threat to your portfolio might be your own brain. The good news is, once you recognize these patterns, you can work to counteract them, or get help from someone who will hold you accountable to your long-term plan (that’s where a trusty financial advisor comes in handy).

Year-End Reflection: Keep the Long View

As we wrap up the year, it’s the perfect time to take stock of your financial journey and mindset. Ask yourself a few pointed questions to gauge where you stand emotionally with your investments.

- How did your portfolio do this year? Are you pleasantly surprised, or a bit disappointed?

- Did you lag the market? If so, do you understand why (e.g. were you more conservatively positioned, or did you hop in and out at the wrong times)?

- Did you take on too much risk? Maybe you swung for the fences and it paid off, or maybe it backfired.

- Are you tempted to sell everything after a great year? Big gains can make us complacent or fearful of losing what we’ve made.

The market will always have good years and bad years. Don’t let a single year’s performance trick you into swinging wildly between fear and greed. Time in the market beats timing the market, and having a steady plan beats reacting to every twist and turn.

As an advisor (and as an investor myself), I know an objective second pair of eyes can be incredibly helpful. Because we’re all human and have those emotional moments, having someone remind you of the big picture – your goals, your time horizon, a bit of historical perspective – can be invaluable.

So go ahead and click the Schedule Meeting button below. Let’s chat about your portfolio, your goals, and how to make sure next year’s financial decisions are guided by calm, informed thinking.